U.S PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT AND PEACE TREATEY IN PORMOUTH by Sergei Witte

It is an open secret that nearly all of Japan’s war loans were floated on the American money market, so that America practically financed Japan in her clash with us. Furthermore, American public opinion, upon the whole, was on our enemy’s side. Such was the situation which I found on my arrival in the United States. (Memoirs p. 140)

My personal behaviour may also account for the transformation of American public opinion. I took care to treat all the Americans with whom I came into contact with the utmost simplicity of manner. When travelling whether on special trains, government motor cars or steamers, I thanked everyone, talked with the engineers and shook hands with them in a word, I treated everybody, of whatever social position, as an equal. This behaviour was a heavy strain on me as all acting is to the unaccustomed, but it surely was worth the trouble. Not only did it not detract from my dignity as the chief plenipotentiary of the Russian Emperor, but on the contrary, greatly enhanced my prestige. The Americans were accustomed to think of an emissary from the autocratic of all the Russia as a forbidden and inaccessible personage, not unlike the other foreign officials who visited the country. And here they discovered not without keen pleasure, that one of the highest dignities of the Russian Empire, the President of the Council of Ministers and the Ambassador Extraordinary of the Emperor himself, was a simple, accessible and amiable man, treating the most humble citizen as his equal. pp. (Memoirs 141-142)

Four days later I cabled the Foreign Minister as follows: We have reached no agreement regarding the payment of indemnities, Sakhalin, the reduction of the navy, and ships in neutral waters. On Monday or Tuesday there will be the decisive session, after which, if neither side yields, we shall have to break the negotiations. What the Japanese think is not known to anyone, I believe. They are impermeable wall even to their white friends… In view of the infinite importance of the matter, it is necessary, it seems to me, to gauge the situation again and to take an immediate decision. I have not the slightest doubt but that a continuation of the war will be the greatest disaster for Russia. We can defend ourselves with more or less success, but we can hardly defeat Japan. The Emperor’s autographed remark on the margin of this telegram: “It was said – not an inch of land, not a ruble of indemnities. On this I shall insist to the end. On August 21st, I cabled the Foreign Minister:

… I believe that after the Conference, when the world learns what happened there, the peace-loving public opinion will recognize that Russia was right in refusing to pay a war indemnity, but it will not side with us on the subject of Sakhalin, for facts are stronger than arguments. As a matter of fact, Sakhalin is in the hands of the Japanese, and we have no means to recover it. Consequently, if we wish the failure of the Conference to be laid to Japan, we must not refuse to cede Sakhalin, after having also refused to indemnify Japan for her war expenditures. If it is our desire that in the future America and Europe side with us, we must take Roosevelt’s opinion into consideration, in giving a final answer. (pp. (Memoirs 154-155)

The following day I received his reply, as follows: Unfortunately, it appears from your last telegram that in spite of the readiness which you manifested in the conferences to come to an amicable agreement on each point; the Japanese plenipotentiaries continue to insist on peace terms, which being incompatible with Russia’s dignity, are altogether unacceptable. In view of this His Majesty has ordered you to cease further conferences with the Japanese delegates, if the latter are not empowered to desist from the excessive demands which they are now making… Thus the negotiations are being broken off because of the intractability of the Japanese as regards the question of indemnities; we must stop then and there. Under these conditions, the further discussion of the altogether inadmissible cession of Sakhalin becomes unnecessary.

True, Sakhalin is at present occupied by the Japanese and we shall not soon be able to dislodge them from the island; nevertheless there is a great difference between a forceful occupation of this territory and a formal documental cession of this island which has a brilliant future. (Memoirs p. 155)

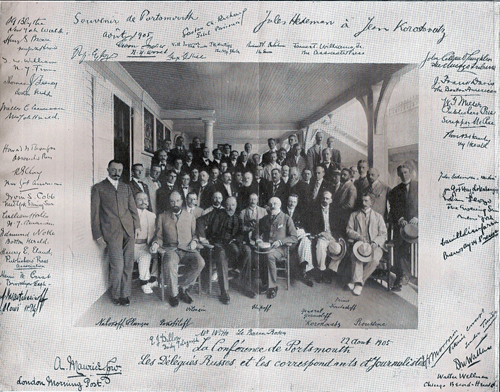

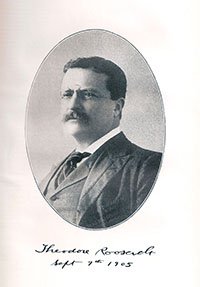

President Roosevelt used his influence with the Japanese delegates to restrain them from pressing their demand for an indemnity, as is witnessed by the two letters following, which came into my possession. These letters as here reproduced are re-translated into English from the translation into Russian as they appear in Count Witte’s papers.

Oyster Bay, August 22, 1905

Dear Baron Kaneko

I deem it my duty to inform you that on every hand I hear doubts, expressed by Japan’s friends, as to the possibility of her continuing the war for a large indemnity. One of the prominent members of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, who absolutely sides with Japan, writes me:

“It seems to me that Japan is hardly in a position to continue the war only for a large indemnity. I would not blame her, if she should break the negotiations for the purpose of occupying the Saghaiien. But if she will resume the military operations exclusively for the purpose of obtaining money, she will not obtain the money and besides she will soon lose the sympathies of this and other countries. I deem in my duty to say that I do not consider her demand for an indemnity just. She has occupied no Russian territory except Sahhalien, and the latter she still has to retain. Your Excellency should understand, I believe, that in America, among people who hitherto were well-disposed toward Japan, a very considerable majority would share the opinion expressed in the above cited lines. The consent to restore the North half of Saghalien gives Japan some hope of getting a certain amount of money in addition to the sums for the Russian war prisoners which are justly, due to her, but I do not think she can demand or obtain anything like the sum which she set as indispensable, namely six hundred million. You know how urgently I advised the Russians to conclude peace. With equal firmness I advise Japan not to continue the war, for the sake of war indemnity. Should she do so, I believe that there will occur a considerable reversal of public opinion against her. I do not believe that this public opinion could have a tangible effect. Nevertheless, it must not be altogether neglected. Moreover, I do not think that the Japanese people could attain its aims if it continued the war solely because of the question of an indemnity. I think that Russia will refuse to pay and that the common opinion of the civilized world will support her in her refusal to pay the enormous sum which is being demanded or anything like that sum. Of course, if Russia pays that sum, there is nothing else for me to say. But should she refuse to pay, you will see that, having waged war for another year, even if you succeeded in occupying Eastern Siberia, you would spend four of five hundred more million in addition to these expended, you would shed an enormous quantity of blood, and even if you obtained Eastern Siberia, you would get something which you do not need, and Russia would be completely unable to pay you anything. At any rate, she would not be in a position to pay you enough to cover the surplus expended by you. Of course, my judgement may be erroneous in this case, but it is my conviction expressed in good faith, from the standpoint of Japan’s interest as I understand them. Besides, I consider that all the interests of civilization and humanity forbid the continuation of the war for the sake of a large indemnity. This letter is, of course, strictly confidential, but I will be glad if you were it to you Government and I hope that you can do it. If the message is transmitted at all, it should be done immediately.

Sincerely yours,

(Signed) Theodore Roosevelt

Oyster Bay, Aug. 23, 1905.

Dear Baron Kaneko,

In addition to what I wrote you yesterday, I wish to bring the following to the attention of the Ambassador in His Majesty the Japanese Emperor:

It seems to me that it is to the interests of the great Nipponese Empire to conclude peace for two reasons: 1st, its own interest; 2nd, the interest of the whole world, toward which Japan has certain duties. You remember, I am not speaking of the continuation of the war for the purpose of keeping Saghalien, which would be right, but of the continuation of the war for the purpose of getting from Russia a large sum of money, which in my opinion would not be right. Of course, it is possible that you may get it, but I am convinced that you would have to pay too dear a price for that success. If you fail to obtain the money, no further humiliation and losses inflicted upon Russia would redeem your expenditures in blood and treasure.

1. It is in Japan’s interest now to end the war. She has acquired domination in Korea and Manchuria; she has doubled her own fleet by destroying the Russian fleet; she has obtained Port Arthur; Talienwan, the Manchurian Railway; she has obtained Saghalien. There is no advantage for her in continuing the war for money for the continuation of the war would absorb more money than Japan could in the end get from Russia. She will be wise if she will now put an end to the war with triumph and take her place as a leading member of the council of nations.

2. From the ethical standpoint, it seems to me Japan has a certain obligation toward the world in the present crisis. The civilized world expects from her the conclusion of peace; peoples believe in her; let her manifest her superiority in the question of ethics, no less than in military affairs. An appeal is made to her in the name of all that is lofty and noble, and to this appeal, I hope, she will not remain deaf. (Memoirs pp. 157-158)

With profound respect,

Sincerely yours, (Signed) Theodore Roosevelt

On August 27th I cabled the Foreign Minister:

… In view of the fourteen-hour difference in time, he asked me to call the next session not to to-morrow, but the day after to-morrow (Tuesday). I replied that I did not think I had the right to refuse his request, but I declared to him in a most categorical fashion that we would not in any case or under any circumstance renounce the decisions taken in accordance with His Majesty’s, latest instructions, that this was the last concession granted by His Majesty, and that any new proposal I would reject on the spot without submitting it to my Government. Consequently, I said, if they hoped that we would yield, they were wasting their breath and time and keeping the world in uncertainty.

The Emperor wrote the following remark on the margin of this dispatch:

Send Witte my order to end the parley to-morrow in any event. I prefer to continue the war, rather than to wait for gracious concessions on the part of Japan. (Memoirs p. 158)

Dated Peterhof, August 28, 1905

The following day I could say, in a message to the Foreign Minister;

Before the beginning of to-day’s session, at half past nine, Baron Komura wished to have a private conversation with me. In the course of it I said that, according to instruction I had received, to-day’s session must be the last one and that the only thing left to them is either to accept or reject the final and irrevocable decision of the Emperor. I am almost certain that they will yield to His Majesty’s will.

And later in the day, I conveyed joyful news in the following despatch:

I have the honour to report to your Imperial Majesty, that Japan has accepted our demands regarding peace conditions. Thus peace will be restored owing to your wise and firm decisions and in exact conformity with your Majesty’s plan. Russia in the Far East will remain in Great Power, which she has been hitherto and which she will forever remain. In executing your orders we have exerted all the powers of our intelligence and Russian heart. Graciously forgive us for not having been able to achieve more.

The peace treaty was signed September 5, 1905, at 3 p.m.

On the eve of the last day of the Conference I had been still in the dark as to whether the treaty would be signed by the Japanese. My sleep was obsessed with nightmares and interrupted by intervals of praying and weeping. My mind was a house divided against itself. I was aware that the conclusion of peace was imperative. Otherwise, I felt, we were threatened by a complete dėbâcle, involving the overthrow of the dynasty, to which I was and am devoted with all my heart and soul. I knew I did not bear the slightest particle of guilt for this terrible war. On the contrary, I did all I could to oppose it. Yet it fell to my lot to be instrumental in concluding this treaty, which when all is said, was a heavy blow to our national amour-proper. I knew that all the responsibility for the treaty would be placed on me, for none of the members of the ruling clique, let alone Emperor Nicholas, would confess the crimes they had committed against their country and against God. Naturally, I could not help being greatly depressed. I do not with my worst foe to go through the experiences which were mine during the last days of the Portsmouth Conference. To crown my miseries I was taken ill, but in spite of my illness I had to be constantly in limelight and play the part of a conqueror. Only few of my collaborators understood my state of mind. (Memoirs pp. 159-160)

The following is the text of the letter in which Czar Nicholas informed me of his decision to honour me with the title of Count and expressed his appreciation of my services in successfully concluding an honourable treaty of peace (Memoirs, p. 175):

October 8, 1905

Count Sergei Yulyevich:

In my constant solicitude for Russia’s paeaceful prosperity, I agreed to accept the amicable proposal of the President of the North-American United States for a meeting of Russian and Japanese plenipotentiaries for the purpose of determining the possibility of putting an end to the miseries and horrors of a protracted war, which has already involved so many sacrifices on both sides. My confidence has imposed upon you the mission of going to the United States as my first plenipotentiary and of entering into negotiations should Japan’s terms prove admissible, for the purpose of concluding peace on the basis of principles which I had elaborated with precision. Both in the detailed discussion of the preliminary terms and in the final drafting of the peace treaty you acquitted yourself brilliantly of the task confided to your charge. You acted firmly and with the dignity which befits a representative of Russia, and thus you have obtained just concessions, having demonstrated the inadmissibility of terms which could offend the patriotic consciousness of the Russian people or injure the vital interests of our country. Having duly acknowledged the consequences of the success achieved by our opponent, you have, nevertheless, declined, according to my instructions, to pay in form or another, the expenses for the conduct of the war, which was not begun by Russia, and you have only agreed to return to Japan the Southern part of Sakhalin, which belonged to her prior to 1875. Thus, the task of restoring peace in the Far East has been successfully accomplished for the common good. Highly valuing the skill and statesmanlike experience manifested by you. I herewith bestow upon you the rank of count of the Russian Empire, as a recompense for your high and great service to the country.

I remain unalterably well-disposed to you and sincerely thankful.

(Signed) Nicholas

At Portsmouth I received, among other deputations, a group of representatives from American Jews. The deputation included Jacob Schiff and Seligman; two great bankers, and Oscar Straus, who has in recent years served as American Ambassador to Constantinople. Two years ago this diplomatic conceived a desire to visit Russia. In spite of his high station and the universal respect he enjoys in America he was forced to enter into protracted negotiations with the Russian police and it was only under special surveillance and for a strictly limited period of time that he was allowed to come to Russia. I recorded in detail my conversation with the Jewish delegates in a number of official dispatches which I sent to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and I shall state her merely the substance of the talk. I received them very cordially and listened with attention to what they had to say. (Memoirs, p. 163)

Before I left the United States, President Roosevelt handed me a letter with a request to transmit it to Emperor Nicholas. The missive began by referring to the gratitude His Majesty had previously expressed to the President for his assistance in bringing about the peace. Now, the author of the letter went on, he was asking a favour of His Majesty. The commercial treaty of 1832 between the United States and Russia, the President said, was interpreted by the Americans as providing for the free entrance of all United States citizens into Russian territory, it being understood that limitations of that right were to originate exclusively from the necessity on Russia’s part to protect herself from harm, material and otherwise. As a matter of fact, however the Russians seemed to interpret the treaty in a different spirit. In recent years, the President pointed out, it had become the practice of the Russian Government to discriminate against the American citizens on the basis of religion and refuse admittance to Jews of American allegiance. To this discrimination, President Roosevelt emphatically asserted, Americans would never consent. Therefore the letter concluded, to continue the friendly relations which had been inaugurated by my visit to the United States, it was necessary for the Russian Government to give up the reprehensible practice of excluding the American citizens of Jewish faith from Russia. This letter I transmitted to His Majesty and in due course it reached the Minister of the Interior. In my premiership a special commission was appointed to study the matter. The commission after long deliberations recommended to give up the interpretation of the treaty clause which offended the Americans, but this recommendation led to no practical consequences. In the end the United States Government abrogated the treaty and we lost the friendship of American people. (Memoirs, pp. 174-175)